The Great Walls Damming Tibet

by Clare Harrison The World’s Water Tower

by Clare Harrison The World’s Water Tower

The Tibetan Plateau, with its vast grasslands, high altitude lakes, glaciers and snowy peaks, plays a fundamental role in maintaining the balance of global climatic systems. Known as the ‘Third Pole’,Tibet represents the largest body of ice and permafrost outside of the Arctic and Antarctic regions.The fresh water maintained in Tibet’s ice and snowy landscape represents the beginning of the entire hydrological cycle for much of the Asian continent, with twelve major rivers originating from the plateau. In fact, melt water from Tibet’s glaciers and snowfall provides 40% of the Earth’s population with fresh water.

China’s Strategic Interest

Tibet’s natural abundance of water and mineralshas led to it becoming a battleground for exploitation. To maintain a satisfied and passive populous in the urban centres and to protect ‘food bowl’ regions that provide for some 1.3 billion mouths, China is going to great lengths to secure Tibet’s water sources.

The construction of dams generally serves the purpose of increased control of water distribution to farmland irrigation systems, to better manage the impacts of flooding and to direct water to important areas such as urban and industrialcentres. The other major function of dams is to capture water to generate hydropower energy.Hydropower is the centrepiece of China’s renewable energy strategy which it plans to rapidly expand by 2020 . In order to maintain a good reputation for its climate change mitigation efforts and to reduce the extreme pollution choking its people, China has embarked on a programme of dam-building.

The Dam Situation

Despite the first megadams coming on the scene in the 1970s, the number of new dams being built are at levels not seen before anywhere in the world. With so many in the pipeline, China’s voracity for energy and water consumption is indisputable. A major dam or ‘megadam’ is a major hydroengineering operation which captures water behind a retaining wall of at least 150metres. In a conventional dam this water may be stored in a reservoir, with release controlled to produce dispatchable power. In a Run-of-the-River (ROR) dam, this water may be held in a pondage system (a smaller reservoir system) for intermittent energy production, or the dam may not store water, only channeling river flow to pass through turbines.

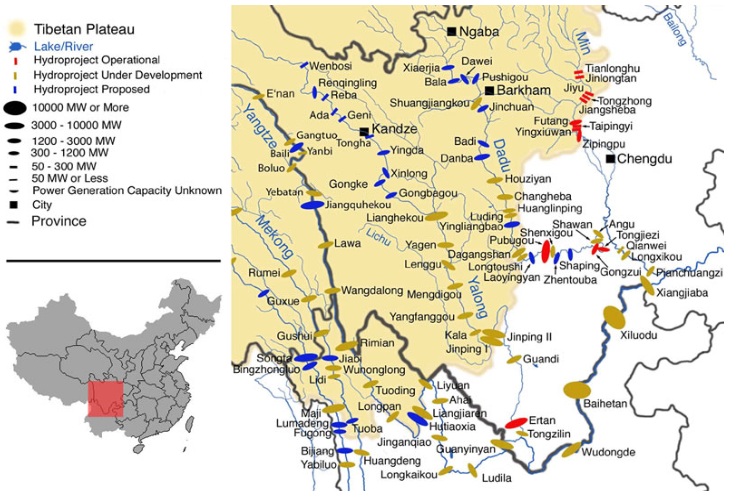

China is upscaling its dam building momentum, with many new megadam hydropower plants underway and proposed for the Nu (Salween), Lancang (Upper Mekong), Jinsha (Upper Yangtze), and the YarlungTsangpo (which becomes the Brahmaputra). In just over a decade more hydropower plants have been installed in China than the rest of the world combined. With 87,000 dams, China now has more than any other country in the world, with twothirds of these located on the Tibetan Plateau .

Record Breaking Great Walls

The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtse river has by far received the most international attention for its current status as the biggest producer of electricity from renewable energy. It is also the largest capacity dam in history. Less attention has been placed on the immense human cost required to produce this engineering feat. This project is responsible for the displacement of at least 1.13 million people in Hubei province, according to official statistics. This dam is additionally responsible for the submersion of 13 cities, 140 towns, and 1,350 villages .

In order to gain perspective of the enormity of China’s ambitions, it is important to understand the scale of the current major works. Described below are a selection of the most significant damming projects affecting Tibetans that are now on the drawing boards or under construction.

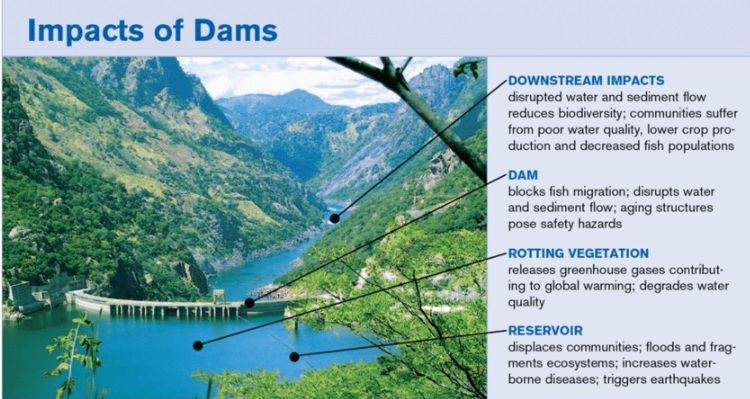

Figure 3. Impacts of Dams summary. Sourced from www.researchgate.net.

Shuang Jiang Kou dam is currently being constructed along theGyelmoNgul Chu (the Dadu River – a Yangtse tributary) within Sichuan Province on the Tibetan Plateau (see figure 2). This is a 312m high embankment dam with a 3.1bn m³ reservoir and power station and is expected to be the tallest dam in the world when it is completed this year (2018) . As a point of reference, this dam wall will be higher than the Potala Palace (from valley floor to rooftop) and its reservoir is over one-fifth the capacity of Tibet’s holy YamdrokYumtso Lake. The Chinese Ministry of Environment has acknowledged that the project will have a negative impact on rare fish and flora and will affect protected nature reserves . Developers from parent company Guodian continue to argue that mitigating measures will counter these effects. However, doubt has been expressedin the light of themany Chinese engineering projects that have been commenced prior to state approval.

Each major project appears to be another attempt at breaking new records. The Longtan hydropower station in Nanning, in the upper Hongshui river (primarily in Guangxi region), comes close to the Three Gorges Dam in power generating capacity. This dam, which opened in 2009, is reportedly the highest concrete wall and the largest underground industrial complex in the world with a 27.2bn m³ reservoir storage capacity, swallowing up that of Shuangjiangkou. The enormous area affected by this dam, although not on the Tibetan Plateau, has been responsible for the relocation of around 80,000 Tibetans, with proponents claiming it will ease power shortages and raise living standards in the area.

Shigatse, Tibetan Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region’s (TAR) second biggest city and tourist hot spot is will be affected by the construction of a dam as part of the Lalho hydroelectric project along the Xiabuqu river, which joins the Brahmaputra at Shigatse. It was reportedly begun in 2014 and is expected to be completed by 2019. This is causing concern for India, with research underway to more concretely ascertain the comparative contributions of the Tibetan and Indian water catchments to the Brahmaputra. Some experts attest the Tibetan contribution is around 40%. Conversely, others suggest that the Lalho project may not reduce water flow to India in the long run, but it may contribute to desertification in Tibet and the Shigatse region itself.

YarlungTsangpo/Brahmaputra River

The YarlungTsangpo river, with its source at the sacred Mt Kailash, is one of the more controversial river systems to be dammed by the Chinese government. This river becomes the Brahmaputra and is immensely important for the north east of India and is the lifeforce of Bangladesh. Currently along this river system there is the Zangmu power station, built close to Gyaca in the TAR. Although this is a run-of-the-river dam, it holds a daily capacity of 86 million m³ in its pondage reservoir. Despite assurances to India’s northeast and Bangladesh’s water security, there is concern about the plans for more dams and a potential northward rerouting of water at the Great Bend, which flows by Pei, Tibet, through to Arunachal Pradesh . China is proposing another 27 dams along the YarlungTsangpo . This case-by-case impact assessment may show the potential for serious long-term environmental and political consequences.

Nu/Salween River

In 2003 the Chinese government announced it would allow a 13-dam cascade on the Nu River (the Salween in Burma) – the largest cascade of hydroelectric dams in the world . This is a pristine river lying at the heart of the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage Site. However, the UNESCO agreement has not mandated protection of the rivers themselves . The plans have been on and off the drawing boards since their inception, largely due to China’s economic lag and power glut, but also due to effective conservation campaigns which have emphasised the region’s potential for nature tourism as well as its tectonic instability. After a short-lived victory for environmental and local groups in 2013, the pending plans currently stand as five major dams along the immense area from Tibet to the Myanmar border area. One dam is planned in Tibet with four others in Yunnan . Half of China’s recognised minority groups, including Tibetans, reside in this region. It is estimated that up to 50,000people could face resettlementif these plans are to follow through.

Figure 2. Dams constructed or planned along the Yangtse and its three main tributaries. Buckley, M.

(2014). Meltdown in Tibet.

Impacts

Impact of dam building

With half the world’s dams inside its borders, China has paid a huge price for this development. China commenced large scale dam building in 1958 with the Great Leap Forward and many people have died as a result. In an official statement in 2007 by the then Prime Minister, Chinese dams have displaced an estimated 23 million people, and dam breaks have killed approximately 300,000 people .

One such example – of which news emerged despite Chinese censorship – was during the record-breaking summer flood of 2010. The Three Gorges Dam reservoir rose to 12 meters above “alarm level”.To urgently protect the dam its operators opened the floodgates to the maximum. Downstream some 968 people were killed by this inland tsunami, with 507 more missing and economic losses totalled US$26 billion .

Dams have also taken a huge toll on China’s biodiversity, causing fisheries to plummet, threatening important and endemic species such as the endangered giant Chinese sturgeon. In conjunction with other human impacts on rivers, entire species have been driven to extinction, as was the fate of the Yangtze River Dolphin, declared extinct in 2006 . These ramifications of Chinese development by no means represent the full scale of potential impacts to the web of human and ecological systems reliant upon the rivers.

Earthquakes & Landslides

Large dams have been linked to devastating mudslides and landslides. Equally immediate concerns are their role in inducing geological stress which can trigger seismic activity. It is becoming apparent that earthquakes can in fact be induced by dams and globally, there are over 100 identified cases of earthquakes that scientists believe were triggered by reservoirs . With the capture of enormous water bodies, immense pressure is placed on fissures in rock layers leading to widespread instability known as reservoir-induced seismicity . The devastating earthquake of 2008 in Sichuan killed 85,000 people and may have been triggered, or at least magnified by, the 155m Zipingpumegadam, located just 5.5 kilometres from the epicenter . The Chinese government continues to build scores of dams in the country’s most earthquake-prone region on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. This is despite the risks posed to thousands of peopleliving in the path of any surge resulting from dam failure.

Downstream Ecosystem Destruction

China is becoming the ‘ultimate controller’ of the Plateau – the source of water for which nearly half of humanity depends. As Tash Tseri, a water resource researcher at the University of British Colombia disconcertedly states, “The net effect of the dam building could be disastrous. We just don’t know the consequences.” The way in which dams damage river ecosystems is cumulative and the gradual mounting of subtle warning signs can often be ignored. Diversions and alterations in natural river flow put ecosystems under pressure beyond which organisms can adapt. Over time this results in species web imbalances, altered and even dead rivers. In the fragile mountain ecosystems of Tibet, these changes create knock-on effects beyond the rivers that leads to lowered biosystem resilience to unrelenting climatic changes. Human systems reliant upon these rivers will certainly be compromised due to the alterations in crucial ecosystem functions like silt deposition, salinity balance and habitat maintenance. These functions are important for irrigated food cropping systems including paddy rice, as well as for wild fish catch across the entire river system.

Although Chinese government officials and engineering company representatives adamantly claim that ‘Run-of-the-River’ projects maintain flows as before with only a brief storage period, others, including Ramaswamy Iyer, the former Indian Government secretary of Water Resources, point out that water held back even in pondage can result in huge diurnal variations to which aquatic and riparian life are not adapted . Although total daily discharge may be consistent with system averages, the pattern of natural flow fluctuations may not be. These fluctuations are decided upon based on the rise and fall in electricity demand, rather than the requirements of the ecosystem and the livelihoods of people who depend upon the natural cycles of river flow .

The cumulative destructive force of dams to river systems is becoming undeniable in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Entire ecosystems shrinking to the point of complete dysfunction is becoming the norm in these south Asian river deltas. According to research undertaken by the International Geosphere Biosphere Programme, strangulation by dams plays a key role in these processes. The flow into the Indus Delta of Pakistan, sourced at Mt Kailash, is averaging a few hundred kilometres short of meeting the sea, wiping out immensely important mangrove swamps and fish populations . India’s damming of the Ganges has noticeably reduced the water flow into Bangladesh. The increased salinity of soil has adversely impacted agriculture and over the last several decades millions of Bangladeshis have been forced to relocate, many migrating to India’s northeast19.

Forces of Resistance

Tibetans are intimately tied to their environment and take responsibility for its protection. They are a prominent force against the destruction of their sacred mountains, rivers and grasslands. Discontent has arisen as the result of dam construction and the associated relocation of homes and livelihoods. There is strong evidence now that China is ramping up the forced relocation and sedentarisation of various indigenous and nomadic people .

The lives of Tibetans and other ethnic minority groups in China are not being respected as the country’s political and industrial agenda is given priority. “The scale and speed at which the Tibetan rural population is being remodeled by mass rehousing and relocation policies are unprecedented in the post-Mao era,” said Sophie Richardson, the China director at Human Rights Watch. The scale of these relocations and rehousing initiatives is unprecedented. Since 2006, with a focus on the TAR, Chinese authorities have relocated over 2 million Tibetans, whilst in the eastern parts of the plateau, hundreds of thousands of nomadic herders have been settled22. The justification by officials is that these policies are to bring “economic benefits to Tibetans by building modern ‘New Socialist Villages’.”22The speed at which the regime is managing to execute these policies strongly suggests that underlying motivations are closely connected to larger political and development objectives – that is, to ensure no dissident minorities will get in the way of Chinese government and corporation ambitions for resource development and extraction.

The desire of the Chinese authorities to extend control over Tibetans also manifests in a very direct manner. It is well documented that the People’s Armed Police ruthlessly suppresses peaceful protests in Tibet. In by no means an isolated case, in eastern Tibet (Sichuan Province) 10,000 people protested against the Pubugou dam on the Dadu river (see figure 2) after evictions began before the final approval in 2004. Riot police crushed the protest, which was one of the largest rural demonstrations since the PRC’s founding . Since this political action, around 100,000 people, predominantly farmers, have subsequently been displaced from their prime agricultural land by this project, which was completed in 2010.

In opposition to other landgrabs and megadam construction preparations, it has been reported that Chinese forces fire indiscriminately into crowds, make numerous unfounded arrests and in the case of the Pubugou dam, had one of the protest leaders executed . Experiences of violent repression, lack of political freedoms and the trauma of resettlement are becoming more pronounced for Tibetans as the spectrum of development projects broaden. A large number of the individual forms of non-violent protest by Tibetans have been increasingly associated specifically with mining and other developments .

The Politics of Chinese Water Control

The methods China is using to assert itself across the region to extend its own resource security are nothing short of “the greatest water grab in history”, according to the Indian geopolitical analyst Brahma Chellaney. Not only is it damming the rivers on the plateau, it is financing and building mega-dams in Pakistan, Laos, Burma and elsewhere and making agreements to take the power . Although China contends that ‘India has nothing to worry about’, it is clear that by damming all the major rivers sourced from the Tibetan plateau, China will essentially have the power to “turn off the tap to Asia”, stresses Chellaney25. This is a strategic move with potentially global implications.

This east-east neocolonialism that China is extensively engaged in around the world is especially concerning given the apparent apathy towards information sharing, let alone strategic co-design, with downstream nations. When the stakes are so high and international interests are extremely interwoven “even denial of hydrological data in a critically important season can amount to the use of water as a political tool,” warns Chellaney . If China does not share data and show integrity in its willingness to engage in a serious dialogue with India and downstream nations, suspicions and fear will deepen tensions between these global superpowers.

Now the repercussions of China’s pursuits are inseparable from the international arena, pressure upon the government for greater transparency will mount in the face of China’s history of closed doors and censorship. With corruption evident throughout the PRC and transparency far from a priority, statements made by Beijing about operations in Tibet are often deemed unreliable. Given the increasing interdependence, affected nations are going to start asking more questions and demanding more answers. As Gabriel Lafitte warned in his extensively researched work Spoiling Tibet, “by far the biggest impact that mining has had on Tibet – both the land and its people – has no existence officially” .

India’s engagement in this eco-geopolitical conundrum has been to launch an apparent dam “arms race”. As China plans to divert water from Tibet and the south west to support the dry, populated north, India is devising water transfers from the water-rich north to the dry south. India is pursuing major dam building operations to achieve greater water security. This could provide short-term gain but in the long term, has the potential to leave entire ecosystems and populations destitute. How these nations pursue relations will determine their abilities to support their enormous populations in the future.

Suggestions for a Way Forward

The United Nations has longsince agreed upon the necessity of greater international protection for downstream nations. These ecological and political relationships are now at crisis point: it is important thatinternational leaders and campaigners push for negotiations. Spearheading the Tibetan voice on these matters is the Central Tibetan Administration who launched a campaign in time for the 2015 Paris Climate Conference. Here they urged world leaders to put Tibet on the agenda. They also used the opportunity to call for China to sign the UN water convention that would commit it to protecting the quantity and quality of its water resources .

Advocacy and education on the true impacts of hydroelectricity need to be more widely dispersed. The blind faith in renewable energies needs to come to an end and must be analysed from a whole-systems perspective to understand the full impact for now and generations to come. Environmentalists and politicians alike should put greater emphasis on less destructive forms of renewable energy such as solar and wind technologies. China is on its way to dominating the global markets for the manufacturing of these products. These forms of renewable energy would be ideal for the Tibetan Plateau as is being demonstrated in Ladakh, said to be “the largest off-grid renewable energy project in the world”29. Most importantly, the environmental and social consequences of these technologies are arguably far less than of hydropower and should be strongly campaigned for.

The great scope of work done by the hundreds of organisations globally who spread the word of Tibet and its guardian people needs to consciously integrate an awareness of all aspects of development connected to the political and environmental context, as it unravels. The dispersion of awareness of the developments underway in Tibet, such as these colossal damming operations, being as transnational as they are, is important for the realisation of global interconnectedness. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama highlights so well, “this blue planet is our only home and Tibet is its roof. The Tibetan plateau needs to be protected, not just for Tibetans, but for the environmental health and sustainability of the entire world.”

References:

Tianjie, M. (2017, January, 14). China’s Ambitious New Clean Energy Targets. The Diplomat. Retrieved fromhttps://thediplomat.com/2017/01/chinas-ambitious-new-clean-energy-targets/

Palmo, D. (2016, September 23). China’s Damming of the River: A Policy in Disguise. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2016/09/chinas-damming-of-the-river-a-policy-in-disguise/

Three Gorges Dam. International Rivers.Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/three-gorges-dam

ChinCold. Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Project. Chinese National Committee on Large Dams. Available at http://www.chincold.org.cn/dams/rootfiles/2010/07/20/1279253974125603-1279253974127236.pdf

Reuters. (2013, May 17). China gives environmental approval to country’s biggest hydro dam. Environment.Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-hydropower/china-gives-environmental-approval-to-countrys-biggest-hydro-dam-idUSBRE94G04E20130517

Moore, M. (2008, October 14). China plans dams across Tibet.The Telegraph, Shanghai. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2008/10/china-plans-dams-across-tibet/

ClearIAS. (2016, October 22). China’s Lalho Dam Project: Should India Worry? Retrieved from https://www.clearias.com/lalho-project/

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved fromhttp://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Hussain, W. (2014 December 1). India-China: Securitising Water. Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies. Retrieved from http://www.ipcs.org/article/india-the-world/india-china-securitising-water-4760.html

Yardley, J. (2005, December 26). Seeking a Public Voice on China’s ‘Angry River’. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/26/world/asia/seeking-a-public-voice-on-chinas-angry-river.html

The Mekong Eye. (2017, February 23). Will Hydropower turn the tide on the Salween River? The Mekong Eye. Retrieved from https://www.mekongeye.com/2017/02/23/will-hydropower-turn-the-tide-on-the-salween-river/.

National Geographic. (2016, May 12). China May Shelve Plans to Build Dams on Its Last Wild River. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/05/160512-china-nu-river-dams-environment/.

Yardley, J. (2007, November 19). Chinese Dam Projects Criticized for Their Human Cost. The New York Times.Retrieved fromhttps://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/chinese-dam-projects-criticized-for-their-human-cost-2978

Lewis, C. (2013, November 4). China’s Great Dam Boom: An Assault on its River Systems. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/11/chinas-great-dam-boom-an-assault-on-its-river-systems/

International Rivers. (2011, February 28). China’s Government Proposed New Dam Building Spree. International Rivers. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/china%E2%80%99s-government-proposes-new-dam-building-spree-3419.

Gupta, H. K. (2002). A review of recent studies of triggered earthquakes by artificial water reservoirs with special emphasis on earthquakes in Koyna, India. Earth-Science Reviews, 58(3-4), 279-310. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012825202000636

International Rivers. (2008, June 25). Sichuan Earthquake Damages Dams, May be Dam-Induced. International Rivers. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/sichuan-earthquake-damages-dams-may-be-dam-induced-3619.

Buckley, M. (2014). Meltdown in Tibet. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Vidal, J. (2013, August 10). China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/08/china-and-india-water-grab-dams-put-ecology-of-himalayas-in-danger/.

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Palmo, D. (2016, September 23). China’s Damming of the River: A Policy in Disguise. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2016/09/chinas-damming-of-the-river-a-policy-in-disguise/

Buckley, M. (2014). Meltdown in Tibet. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Human Rights Watch. (2013, June 27). China: End Involuntary Rehousing, Relocation of Tibetans. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/27/china-end-involuntary-rehousing-relocation-tibetans

Lewis, C. (2013, November 4). China’s Great Dam Boom: An Assault on its River Systems. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/11/chinas-great-dam-boom-an-assault-on-its-river-systems/

Yardley, J. (2007, November 19). Chinese Dam Projects Criticized for Their Human Cost. The New York Times. Retrieved fromhttps://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/chinese-dam-projects-criticized-for-their-human-cost-2978

Kyi, D. & Holland, L. (2016, March 14). The Lonely Resistance: Protesting Chinese Resource Exploitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Carnegie Council. Retrieved from http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/ethics_online/0115

Vidal, J. (2013, August 10). China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/08/china-and-india-water-grab-dams-put-ecology-of-himalayas-in-danger/.

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Lafitte, G. (2013). Spoiling Tibet. New York, USA: Zed Books.

Kyi, D. & Holland, L. (2016, March 14). The Lonely Resistance: Protesting Chinese Resource Exploitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Carnegie Council. Retrieved from http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/ethics_online/0115

Tianjie, M. (2017, January, 14). China’s Ambitious New Clean Energy Targets. The Diplomat. Retrieved fromhttps://thediplomat.com/2017/01/chinas-ambitious-new-clean-energy-targets/

Palmo, D. (2016, September 23). China’s Damming of the River: A Policy in Disguise. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2016/09/chinas-damming-of-the-river-a-policy-in-disguise/

Three Gorges Dam. International Rivers.Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/three-gorges-dam

ChinCold. Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Project. Chinese National Committee on Large Dams. Available at http://www.chincold.org.cn/dams/rootfiles/2010/07/20/1279253974125603-1279253974127236.pdf

Reuters. (2013, May 17). China gives environmental approval to country’s biggest hydro dam. Environment.Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-hydropower/china-gives-environmental-approval-to-countrys-biggest-hydro-dam-idUSBRE94G04E20130517

Moore, M. (2008, October 14). China plans dams across Tibet.The Telegraph, Shanghai. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2008/10/china-plans-dams-across-tibet/

ClearIAS. (2016, October 22). China’s Lalho Dam Project: Should India Worry? Retrieved from https://www.clearias.com/lalho-project/

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved fromhttp://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Hussain, W. (2014 December 1). India-China: Securitising Water. Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies. Retrieved from http://www.ipcs.org/article/india-the-world/india-china-securitising-water-4760.html

Yardley, J. (2005, December 26). Seeking a Public Voice on China’s ‘Angry River’. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/26/world/asia/seeking-a-public-voice-on-chinas-angry-river.html

The Mekong Eye. (2017, February 23). Will Hydropower turn the tide on the Salween River? The Mekong Eye. Retrieved from https://www.mekongeye.com/2017/02/23/will-hydropower-turn-the-tide-on-the-salween-river/.

National Geographic. (2016, May 12). China May Shelve Plans to Build Dams on Its Last Wild River. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/05/160512-china-nu-river-dams-environment/.

Yardley, J. (2007, November 19). Chinese Dam Projects Criticized for Their Human Cost. The New York Times.Retrieved fromhttps://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/chinese-dam-projects-criticized-for-their-human-cost-2978

Lewis, C. (2013, November 4). China’s Great Dam Boom: An Assault on its River Systems. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/11/chinas-great-dam-boom-an-assault-on-its-river-systems/

International Rivers. (2011, February 28). China’s Government Proposed New Dam Building Spree. International Rivers. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/china%E2%80%99s-government-proposes-new-dam-building-spree-3419.

Gupta, H. K. (2002). A review of recent studies of triggered earthquakes by artificial water reservoirs with special emphasis on earthquakes in Koyna, India. Earth-Science Reviews, 58(3-4), 279-310. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012825202000636

International Rivers. (2008, June 25). Sichuan Earthquake Damages Dams, May be Dam-Induced. International Rivers. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/sichuan-earthquake-damages-dams-may-be-dam-induced-3619.

Buckley, M. (2014). Meltdown in Tibet. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Vidal, J. (2013, August 10). China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/08/china-and-india-water-grab-dams-put-ecology-of-himalayas-in-danger/.

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Palmo, D. (2016, September 23). China’s Damming of the River: A Policy in Disguise. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved fromhttp://tibet.net/2016/09/chinas-damming-of-the-river-a-policy-in-disguise/

Buckley, M. (2014). Meltdown in Tibet. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Human Rights Watch. (2013, June 27). China: End Involuntary Rehousing, Relocation of Tibetans. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/27/china-end-involuntary-rehousing-relocation-tibetans

Lewis, C. (2013, November 4). China’s Great Dam Boom: An Assault on its River Systems. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/11/chinas-great-dam-boom-an-assault-on-its-river-systems/

Yardley, J. (2007, November 19). Chinese Dam Projects Criticized for Their Human Cost. The New York Times. Retrieved fromhttps://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/chinese-dam-projects-criticized-for-their-human-cost-2978

Kyi, D. & Holland, L. (2016, March 14). The Lonely Resistance: Protesting Chinese Resource Exploitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Carnegie Council. Retrieved from http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/ethics_online/0115

Vidal, J. (2013, August 10). China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger. Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/2013/08/china-and-india-water-grab-dams-put-ecology-of-himalayas-in-danger/.

Ramachandran, S. (2015, April 3). Water Wars: China, India and the Great Dam Rush. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/water-wars-china-india-and-the-great-dam-rush/.

Lafitte, G. (2013). Spoiling Tibet. New York, USA: Zed Books.

Kyi, D. & Holland, L. (2016, March 14). The Lonely Resistance: Protesting Chinese Resource Exploitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Carnegie Council. Retrieved from http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/ethics_online/0115

When are the Chinese honing to ufate this oldap on fans beung used and under construction